Our Poet Theologian in Virtual Residence, Hannah Stone, reflects on time in lockdown as a period we share with all on the same journey, asking us to consider if we have commodified time:

We hear some talk today about how much more time we have in lockdown, and accounts of all the things people are doing that they didn’t have time for before – turning out kitchen cupboards, sorting old photos, tidying gardens. There was some controversy recently when a yoga guru suggested that if you didn’t use this extra time to learn a new skill it wasn’t that you were too busy before, it was that you lacked discipline. That was an unwelcome message for people concerned with the mental health implications of the ‘new normal’ and the pressure to be productive, when many of us feel restless, lethargic, or otherwise disinclined to be active. And for some of us, lockdown and social distancing means additional expenditure of time learning new digital skills; more protracted journeys to work; ‘popping to the shops for a few bits’ has become an expedition requiring planning to queue patiently, two metres apart.

‘Dwell time’ is the phrase used to describe the waiting time of a train in a station while passengers get on and off. It is a necessary stasis between two end points (and likely to become more protracted as restrictions ease somewhat, whilst social distancing remains in place). Maybe lockdown is a sort of dwell time, a period we share with those on the same journey though we may get on and off at different stations.

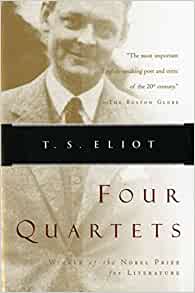

I could be using all my ‘extra time’ to finally get to grips with T S Eliot’s Four Quartets, which circles round time from the opening lines of  ‘Burnt Norton’ onwards:

‘Burnt Norton’ onwards:

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future,

And time future contained in time past.

If all time is eternally present

All time is unredeemable.

As always with TSE, the language is deceptively simple, and the meaning multi-layered. The concept of ‘eternally present’ suggests the practice of mindfulness (to which I shall return on another occasion), but the word that sticks out for me here is ‘unredeemable’. At one level this resonates with Eliot’s recent conversion to Christianity at the time he wrote the poem, a reference to the salvific sacrifice of Jesus on the cross. But it also invokes a sense of getting something back, which led me to think about the commodification of time. So I drafted this:

Dwell Time

Time has not stopped.

Sixty minutes still pace each hour;

as many seconds run to catch up.

It is time to dust off the diary,

to let it fall open at the space called ‘today’,

a place between yesterday and tomorrow.

A passage in which to live.

There are still twenty four hours in each day, no more, no less. Have we commodified time? Do we see it as something we have somehow purchased and need to get value out of? Or is it simply the passing of the hours and minutes we share, in our diverse ways, alongside every other human on the planet?

This is a beautiful poem and sensitive comments about time. I share with you the strangeness of time in lockdown. I think our uncertain future and sense of lost normality makes our relationship with time so much more complicated. Days stretch and shrink, all seem the same and then I lose myself in them completely. Thank you for this lovely writing.